- Home

- Pamela Bell

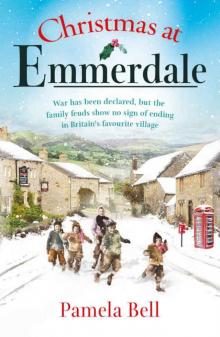

Christmas at Emmerdale

Christmas at Emmerdale Read online

CHRISTMAS AT EMMERDALE

Pamela Bell

Contents

Title Page

1914

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

1915

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Emmerdale 1918: Factual Overview for the Book

Copyright

My thanks go to Linton Chiswick for the storylines and Ollie Tait, Alice Lee and Izzy Charman at Lambent Productions for their part in unearthing stories that inform the novel and the ITV factual series, Emmerdale 1918.

1914

Chapter One

Maggie wedged the basket of eggs on her hip as she wrestled the barn door closed. Bustling past her, Toby gave a woof of pleasure as he spotted a familiar figure and she turned to see her father across the farmyard. His walking sticks rested against the dry-stone wall and he was hanging onto the rickety gate to keep himself upright as he gazed longingly across the valley.

Maggie’s sigh blended exasperation with admiration. Albert Oldroyd could barely walk, barely speak, and still he insisted on dragging himself outside every day despite being told that he couldn’t manage on his own.

And they called her stubborn and proud.

‘You’re a right chip off t’block,’ Joe had commented once. It was one of the nicest things he had ever said to her.

It was a bright day but cool for early July and Maggie was glad of the shawl she had thrown around her shoulders earlier as she followed Toby across the farmyard. He was a bristly, long-legged terrier – not the prettiest of dogs – but with bright eyes, a cold black nose and a sweet nature that more than made up for his lack of looks.

A brisk wind was shoving great clouds across the Yorkshire sky, sending shadows sweeping over the fells on the far side of the valley and dazzling with sudden bursts of sunlight. It snatched at her carelessly pinned-up hair and she swiped the strands away from her face with the back of her wrist.

Toby frisked around her father, nearly unbalancing him before Maggie called him sharply and he nosed instead under the gate onto the track. Hemmed in by two mossy stone walls and overhung in places by oaks, elderflower bushes and dog roses, the track led down to the lane into the village. A quagmire of mud in winter, it was lush now with feathery summer grass and Toby snuffled happily among the buttercups.

Maggie balanced the basket of eggs on the gatepost so that she could take her father’s arm. ‘You shouldn’t be out here, Pa,’ she said, knowing that she was wasting her breath. ‘You’ll get cold.’

Albert’s eyes were fixed on the fell opposite. She followed his gaze across Beckindale, a huddle of grey stone houses in the curve of the beck, to rest on the long, low farmhouse settled into the fold of the hillside beyond.

High Moor.

‘Wish … go … home …’ Albert’s words were forced out with agonising effort, and so slurred that only Maggie could understand him, and her heart clenched in sympathy.

‘I know,’ she said, her throat aching. ‘I’d like to go home too, Pa, but we can’t. The bank has sold High Moor to pay off our debts, remember?’

Now strangers owned the great iron key that sat, never used, in the front door of the farmhouse that had been built by her grandfather’s grandfather. Strangers would be learning about the stair that creaked and the way the sunlight spilt onto the landing on summer mornings. They would stand at the parlour window and watch the rain racing across the fells, skimming over the long lines of the dry-stone walls and sweeping up and over the tops. They could step into the early morning dew and listen to the skylarks soaring over the heather and the distant bleating of the sheep dotting the hillsides, far from the squash and squabble of village life.

A tear squeezed out of the corner of her father’s eye. ‘Sorry,’ he managed.

‘It’s all right, Pa,’ said Maggie gently.

‘Not … right …’ The gate to the farmyard hung drunkenly from the post. The wood was rotten, the iron hinges rusting, the broken sneck held in place with frayed binder twine. When her father’s grip on it shook in frustration, the whole gate lurched forwards and Maggie only just managed to haul him back before he fell.

‘Pa, be careful! You know what this gate is like.’

She had tried asking Joe to fix the gate once, when she had been a new wife and had thought she could change things at Emmerdale Farm.

Joe had soon put her right about that.

Maggie sighed, remembering. She knew that the state of the farmyard must be distressing to her father, who had run a tight ship at High Moor until his collapse, but they had had nowhere else to go.

Emmerdale Farm had been their only option.

Without meaning to, she glanced down to the right, where Miffield Hall stood half hidden in the trees. Once she had thought there might have been another choice, but she had soon been put right about that, too.

‘Ralph is not for you, Margaret.’ Lady Miffield could not have been clearer. She hadn’t bothered to lower her voice as the congregation milled around outside the church, most listening avidly to Maggie’s humiliation at the hands of Ralph’s stepmother. ‘The marriage wouldn’t be successful. In the long run, you would be much happier with someone of your own class, and so would Ralph.’

‘To hell with them.’ White with fury, Ralph had come to find Maggie when he heard what his stepmother had done. ‘They can’t stop us getting married. We’ll go away tonight.’

‘And go where?’ Maggie had asked dully.

‘America! Australia! Anywhere!’

‘And Pa? He’s too ill to travel. I can’t leave him, Ralph. Not now.’

Leaving High Moor was going to break her father’s heart, Maggie knew. She couldn’t take him away from Beckindale too, but where could they go? They had no money, no family, and isolated as they had been, few friends. Lord Miffield owned most of the land around the village and he was not inclined to rent so much as a cottage to a young woman who had, according to his wife at least, tried to seduce his eldest son and heir away from a sense of what was right and fitting.

And then there had been Joe Sugden, twisting his cap between his hands. His family had emigrated, leaving him Emmerdale Farm. He needed a wife, he said. He would give her father a home.

Ralph went out and got drunk when he heard. A week later, he left Miffield Hall.

There were those in Beckindale who felt Maggie had got above herself. They viewed her downfall with the satisfaction of those proved right in their predictions: Margaret Oldroyd would get what she deserved. They had been quick to pass on the rumours from Miffield Hall over the past year. Ralph was in New York, wooing an American heiress. Ralph was holidaying on a yacht in the Mediterranean. Ralph was shooting with the King at Sandringham.

Whatever he was doing, Ralph was a very, very long way from Beckindale. From Maggie.

She swallowed down the memory and made herself look away from Mif

field Hall, only to find her father watching her and clearly able to read her unguarded expression.

‘You …’

It was terrible watching his face contort with the effort of speaking.

‘… here … sorry …’

‘Oh, Pa …’ Maggie couldn’t bear the anguished guilt in his eyes. He blamed himself for his seizure, for letting High Moor go, for her decision to marry Joe. She mustered a smile ‘It’s not so bad, is it? We’ve got each other,’ she reminded him. ‘We’ve got Toby,’ she added as a pheasant burst out of the long grass with a loud rattle, outraged at having been disturbed, and the dog recoiled in comical shock.

The corner of Albert’s mouth twitched in an attempt at a smile. Encouraged, she tucked her hand into the crook of his arm. ‘Remember what you used to say to me and Andrew? That all we could do was to keep our promises and keep our heads up? Maybe Emmerdale Farm isn’t what I dreamed of – what either of us dreamed of – but I’m not going to start weeping and wailing. I’m going to keep my head up, just like you taught me to.’

‘My … girl … proud.’

Maggie wasn’t sure if her father was telling her that he was proud of her, or if being proud was her problem. Perhaps it was. Ralph had used to tease her about being too proud. ‘I love it when you look down your nose at me,’ he had said. ‘It makes me realise that the Verneys are Johnny-come-latelies to Miffield Hall, while the Oldroyds have been at High Moor for ever.’

Disguising her sigh with a smile, Maggie kissed her father’s cheek, hating how papery his skin felt. ‘Come on, Pa. I don’t want you catching a chill. Let’s get you inside.’

Toby came bounding back at her whistle and wriggled under the gate to fawn adoringly at her skirt as she picked up the eggs and tucked one of her father’s sticks under her arm so that she could help Albert back to the house. He was terrifyingly frail and light, and his hand trembled alarmingly on his stick. Very, very slowly they made their way across the farmyard, picking their way through the stale puddles that gleamed in the bright light.

Emmerdale farmhouse was a long, grey stone building, so old it seemed to sag into the ground. The dairy Maggie had made her own stood between the farmhouse and the cow byre where the cows were milked. A cartshed, a stable, an empty pigsty and a barn, all in various stages of dilapidation, formed the other sides of a rough square. A mess of rusting wire, broken wheels and pieces of wood cluttered the doorways and were guarded by a tangle of nettles and bindweed. In one corner of the yard, a muck heap sprawled, turning the cobbles slick and slimy with manure whenever it rained. Maggie wrinkled her nose at the stink of it. At least the wind was blowing the flies away today.

‘I haven’t got time to pretty up t’farmyard for you,’ Joe had warned his new bride. ‘You stick to the kitchen where you belong, and we’ll get on.’

After the brightness outside, the kitchen seemed very dark and until Maggie’s eyes adjusted all she could hear was the bad-tempered thump as Dot slammed the washing-dolly into the clothes, and the splash of water sloshing over the edge of the tub onto the flagstone floor.

Maggie knew she was lucky to have help in the house. There was no way she could do all the tasks that fell to a farmer’s wife and care for her father at the same time. Besides, Dot was an excellent cook, while Maggie couldn’t even manage the oatcakes that were staples in any Yorkshire farmhouse. Dot had stared at the burnt and crumbling mess on the iron griddle in disbelief.

‘Ent nobody never taught you how to make havercake?’

‘We had a cook at High Moor. I never learnt how to cook.’

Maggie imagined Dot regaling the gossips of Beckindale with mocking accounts of her inadequacies in the kitchen. She could almost see her lifting her nose with her finger and mimicking ‘we had a cook’.

At least Dot went home in the evenings, unlike Joe’s farm labourer, George Kirkby, and the farm lad, Frank Pickles, who had rooms above the stable. They might view her with a mixture of suspicion (George) and alarm (Frank) but at least they didn’t treat her with the patronising contempt meted out by Dot. At seventeen, Dot was three years younger than Maggie, but that didn’t stop her criticising or pointing out that growing up at High Moor had made Maggie a hopeless farmer’s wife.

Maggie didn’t need reminding. She had spent the year since her marriage to Joe Sugden learning how to do all those things she had taken for granted at High Moor, where her father had had a cook and maids and a shepherd and farmhands. Joe had George and Frank to help with heavy work on the farm, but Maggie had to cook and to bake and make butter and cheese. She had to feed the hens and salt the bacon. She had to wash and iron and mend. To clean out the range and get down on her hands and knees to polish the stone floor. To fetch water from the pump. To empty the slop bucket into the privy every morning.

And when Joe turned to her in bed and pushed up her nightgown, she had to lie there and let him grunt and thrust inside her. Because she had married him and that was what she had promised to do.

Keep your promises. Keep your head up.

Ignoring Dot’s impatient tsks, Maggie helped her father into his chair by the range and tucked him in with a blanket. ‘Comfortable?’

His face worked. ‘Thank … you.’ It came out as ank oo.

Maggie set her jaw against the grief that barrelled through her whenever she remembered her father’s intelligence and quick wit, the jokes and puns he and her brother had delighted in. He had been such a strong personality, with a vivid presence and a warm smile that had made High Moor a golden place.

Until Andrew came in from the fells that day, rubbing his neck. ‘I’ve got a sore throat,’ he said. Four days later, he was dead, and Albert Oldroyd had never been the same again.

‘I’d better give Dot a hand with the washing.’

Monday was wash day. All the dirty clothes from the previous week had to be pounded in the tub, then rinsed and put through the mangle before being hung out to dry. It was a task that took the two of them all morning and Maggie was glad of the chance to escape the dark and dingy farmhouse when it came to hanging out the washing in the unkempt garden. Toby came with her to lie in the grass and sniff happily at the wind while the damp clothes snapped and billowed on the line.

Maggie was pegging out the last of Joe’s shirts when she saw Toby’s ears prick up and a few moments later she heard the cursing as Joe struggled to open the gate he could never be bothered to mend.

Her husband was back.

He had taken the carthorse, Blossom, into the smithy in Beckindale for a new shoe. Maggie suspected that he would have passed the time drinking in the Woolpack while Will Hutton, the taciturn farrier, dealt with Blossom. She braced herself for her husband to be in a surly mood when she went back into the kitchen, but for once he seemed almost genial as they sat down for dinner with George, Frank and Dot. Her father hated being fed like a baby so Maggie helped her father eat later when the others had gone.

‘Any news in the village?’ she asked Joe as she poured herself a cup of tea.

At twenty-five, Joe Sugden was a thick-set, sandy-haired man with ruddy cheeks. It could have been worse, Maggie often told herself. Her husband wasn’t hideous, but his attitude veered between lust and a kind of resentful contempt that made him unpredictable and she had learned to treat him warily.

‘Aye, some,’ said Joe, shovelling potatoes into his mouth. ‘The vicar talked my ear off about some foreigner, Archduke somebody or other, getting shot in a godforsaken foreign place I’ve never heard of. Vicar reckons it means war.’

‘War?’ Maggie looked up sharply as she helped herself from the plate of cold beef. ‘Why?’

‘Summat to do with Russia and Austria, Germany mebbe …’ Joe wiped his mouth with the back of his hand. ‘I stopped listening,’ he admitted. ‘Charles Haywood is an old windbag and probably wrong. It’s nowt to do wi’ us anyroads.’ He removed a piece of gristle from his teeth. ‘Vicar had other news, too.’

‘Oh?’

‘He’d j

ust come from Miffield Hall.’

Maggie stiffened. She had made no secret of the fact that she had loved Ralph. Joe had known that when they married. He had said that he understood. But now when her eyes met his, it seemed to her that his smile was rife with malice.

‘Aye,’ he answered her unspoken question. ‘Ralph Verney’s back.’

Chapter Two

Rose Haywood took a dainty sip of tea and surveyed the parlour at Emmerdale Farm with interest. It was not a welcoming room. It had dark, peeling wallpaper and the uncomfortable-looking chairs smelt musty, as if the parlour had been forgotten until it was needed to lay out Albert Oldroyd’s body. Rose wrinkled her nose at the thought. His coffin wouldn’t have been resting on a couple of stools for long. It was too hot to have bodies hanging around, and besides, it was hay-time. Albert had died on the Thursday and been buried in the churchyard of St Mary’s that afternoon.

The decencies were being preserved with a funeral tea, but the men would go back to the fields afterwards. No one wanted to waste the good weather, death or no death. As it was, Rose was surprised at how many people had crowded into the parlour. Mr Oldroyd had been much respected, of course, but he had barely been seen since the seizure that had robbed him of speech and left him paralysed on one side. Rose suspected that people were more interested in getting a look at Emmerdale Farm.

That was why she had come after all, Rose owned to herself. As vicar, her father had taught his three children to be aware of their own faults, and Rose knew that curiosity was her besetting sin. But Emmerdale Farm had always seemed a kind of Bluebeard’s chamber to her, at once alarming and intriguing. As children, Rose and her brothers had dared each other to go into the farmyard, but more often they had ended up running past the gate. There was something about the overgrown farmyard that appealed to Rose’s romantic nature and she was intensely curious about what lay behind the firmly closed front door of the house.

And clearly she was not alone. Someone had managed to push open one of the windows, but the press of bodies was stifling and Rose could feel sweat trickling inside her corset. The cold meats laid on the table were curling in the oppressive heat. The last week had been one of the hottest she could remember. Every day, the sun had glared down, turning the limestone tops of the fells an eerie white and the normally muddy tracks to dust, and curdling tempers. Even her affable papa had snapped at their maid, Mildred, the day before.

Christmas at Emmerdale

Christmas at Emmerdale